2001 unpublished paper: Travels through the imagination: Future visions of VR & related technologies, Young VR Investigators’ Conference, KAIST South Korea

Erik Champion, M.Arch, M.Phil (hons)

- 2001 Ph.D candidate in Architecture and Geomatics, University of

- SPIRT Industry sponsor: Lonely Planet

The below abstract is derived from research into VR, web technology and GIS/GPS possibilities for a combined Lonely Planet and University of Melbourne digitally simulated cultural tourism project.

Abstract

The research question driving my own research is the following:

- Which varying modes of interactivity add to the experienced significance of and engagement in, a virtual tourist environment?

- Do inbuilt evaluation mechanisms compare favourably to more traditional feedback mechanisms when gauging engagement in an interactive virtual environment?

This research question is a direct result of an extended analysis as to which factors are hindering virtual environments. In this paper I argue that VR (or, as I refer to it here, Virtual Environments), before it can go forwards, needs to address several issues that have prevented widespread dissemination of its potential.

The issues that needs to be addressed are:

- Accessibility, which includes terminology and classification, and collaboration between related disciplines especially between designers and those that evaluate the psychological effects of virtual presence on the participants.

- Interactivity, between the virtual actor, environment, object and task; social interaction; and messaging between actors.

- Dynamic histories, with annotation; as well as augmentation between fact fiction and imagination.

After discussing what I think needs to be done, the paper ends by describing a virtual environment prototype using inbuilt evaluation mechanisms to gauge the effect of various forms of interactivity on user engagement. The findings will hopefully be of particular interest to virtual heritage, cultural tourism, and archaeological or even anthropological digital simulations.

Virtual environments are too often driven by technological advances (technology for technology’s sake). Perhaps important at the start of the era (if there was a start to the era), now we need to have goals and aims for modelling, if only to have some idea of what is worthwhile downloading from Internet depositories.

In order to satisfy users, the tourists of a virtual environment, they need to know the goals-why they should immerse themselves in virtual environments.

Roughly, virtual environments may be created to:

- Promote technology for the sake of technology (product showcases). You can see such various examples on the websites of Shout3d, Pulse3d, Wild Tangent, Blaxxun, MindAxel, etc.

- Enhance motor-coordination and related physical skill, especially in games. Some of the best examples of Macromedia’s Director Studio 8.5 are the three-dimensional shooter games.

- Synergise learning through the use of various multimedia, for example, Alias Wavefront’s Maya has been used to create models of the human heart in action, as well as show to service a car’s engine.

- Preserve cultural artifacts via a three or even four-dimensional record of history.

For example, UNESCO’s World Heritage Site and the Virtual Heritage Society’s site.

- Present ideas objects or techniques difficult to perceive or conceive of in real-world form, or in conventional media. This can range from Japanese construction details to electric waves transmitted through the human brain or even the formation of stars.

- Extend the perceptual experience or perceptual boundaries of observers. Various environmental art ‘happenings’ have been around for decades. A multimedia cinema was proposed as early as the 1950s. Collaboration between sound composers and virtual reality designers is burgeoning; one of the fundamental criterions for acoustics is spatial presence.

- Engender social discussion (although I see little specific benefit so far in three- dimensions). Multi-user chat worlds include, Activeworlds, Outerworlds, Vnet, Cybertown, Blaxxun communities, iCity, Galaxy Worlds et al.

Yet virtual environments are too often only showcases. For example, a major portal for virtual heritage, www.virtualheritage.net, records the most popular articles, not the most popular models. Virtual heritage models are still not considered worthy intellectual content even by societies dedicated to their advancement. Major conservation organisations do not know of the potential of virtual environments to preserve both the formal specifications of the objects, and their cultural associations. The ICOMOS Burra Charter does not list digital media as one of the many listed media to record cultural heritage.1

Terms used in environmental psychology, anthropology and archaeology2 offer a scholarly framework for digital environments; they have been used for qualitative and quantitative analysis across a range of cultures and time zones by a range of academic disciplines.3 Even Information Designers have commented on the usefulness of these terms.4

In terms of analysing interactions in an environment, I propose that terms used in both environmental psychology and in anthropology and archaeology would be suitable. These fields offer a scholarly framework for digital environments due to a focus on

environment-people interaction, cultural behaviour (people-people interaction), and the interaction of people with their culturally defining use and creation of artefacts (people- artefacts interaction).

Schiffer (Schiffer 1999 p16), gives a long list of academics in the social and behavioral sciences using the actor metaphor (including Giddens 1993, Braun 1983, O’Brien et al 1994, Deacon 1997, Goffman 159 and 1974, Hall 1963, McDermot and Roth 1978, Byrne 1995, Nielsen 1995, Walker 1998). Schiffer further extends the actor / performer metaphor as below but in reference to what he calls anthropological archaeology and its attempt to re-focus on people-artefact interactions. The terminology focuses on material culture interaction, using interactor, artefacts, and externs as the basic elements.

Some of the terms include:

- Interaction: Schiffer defines five modes of Interaction. There are: mechanical (both the tactile and changing material substances, which include sound); chemical (photosynthesis, rust, digestion smell etc); thermal (when one interactor cools or warms another); electrical (static shock, medical devices like pacemakers etc); and electromagnetic. The latter Schiffer argues includes “light reflected form and or emitted by artefacts, externs and other people” and thus sight. See also Stanley Coren, Lawrence M Ward and James T Ennis, Sensation and Perception, 1994.

- Interactor: any phenomena that can take part in interactions, which is in a way a circular definition. For more articles on interactors see David L Hull 1998, and Elliot Sober 1984. An interaction must arise from one or more performances by interactors (each interactor has a range of performance characteristics). There are 3 types of interactors: people, artefacts, and externs.

- Compound interactors are made up of people, externs and artefacts. There is either a tendency to act as a single entity, or as macroartifacts, such as a person riding a horse (Schiffer 1999 p13).

- “Artifacts are phenomena produced, replicated, or otherwise brought wholly or partly to their present form through human means”. (Schiffer 1999: p12; Rathje and Schiffer in 1982). Types of artefacts are platial (“reside in a place… include portable artifacts stored there.”), personal artefacts (actual or temporarily associated with the human body), and situational artefacts (“arrive with people or turn up at a place for the conduct of an activity”) (Schiffer 1999: pp21-22).

- Externs “takes in phenomena that arise independently of people, like sunlight and clouds, wild plants and animals, rocks and minerals, and landforms” (Schiffer, 1999).

- Traces: Another term Schiffer uses is the formal trace, properties of material that have been modified. For example, by analysing food residue left in a pot, archaeologists can infer that it was used for cooking rice.

- A life history is the specific sequence of interactions and activities that occurs during a given interactor’s existence ”. .Sets of closely linked activities are called processes, which in turn are subsets of life histories.The theory is also based on interactivity, allows for interaction independently of humans, and allows for quantifiable research insofar as there can be discrete (i.e., observable) interactions. Weaknesses may include an over generous definition of materiality (materiality seems to include everything), and an inability to discern mental states of actors in a virtual environment (due to its behavioral focus).

A major part of Schiffer’s theory relies on a three-way means of communication (Schiffer 1999: p59); information is transmitted person to person via artefacts, not directly person to person (‘receiver-sender’) as in linguistic theories. A person modifies an artefact, which is decoded eventually by an archaeologist’ s ‘relational knowledge’. There are thus three interactors.

In a virtual environment that simulates a past culture, the ability to code and relay information through interactions with artefacts is surely as useful if not more so as interacting directly with computer-based agents. It is more authentic in the sense that much of our information of past people does actually come to us via inferences (which Schiffer calls correlons), than through actual people or direct representations of people.

Possibly more communication between disciplines, such as projects between cultural anthropologists, environmental psychologists testing criteria of presence, and virtual environment designers, would help towards creating engaging virtual environments.

Certainly, a common terminology as discussed above, but also listing design goals, intended audiences, environment elements, interactive methods used etc., would help focus attention on creating content, rather than mere form.5

Formalism versus Interaction in Virtual Environments

Current thinking in the design of digital places – particularly those available over the Internet – is to create a series of objects. People can move around, and in some cases pick up or focus on objects. Generally, only one observer can view the environment at any one time. Objects in these worlds might have hyperlinks, but no other interactive ability.6

Multi-user three-dimensional chat rooms are often less advanced than two-dimensional chatrooms. The objects in these chatrooms likewise lack purpose for anything more meaningful than to vary the backdrop.7

Technological advances rather than content seem to be the main motivating factor of many web-enabled environments. To some extent, this may have been encouraged by limitations of early software, but even though both hardware and software are increasing in power and flexibility, new and more effective means of interaction are yet to appear.

Another factor may have been a belief that we experience reality as something objective, settled and constant. Solid and immutable objects may be easier to conceptualize and model than what reality is really made up of. That is, dynamic webs of social behaviours and mental states, belonging to unique and individually specialized inhabitants as well as a huge array of artefacts, waves of various energy sources and particles of matter.8

Further, everything in our head is put into a conceptual schema, a framework. Without content relating directly to how we as social agents perceive the world, an emphasis on formal realism is not creating a Virtual Reality, but a storehouse of visually represented objects.

Social behaviour is behaviour between two or more people, cultural behaviour is a subset of social behaviour, where behaviour is governed by or understood in terms of a cultural setting. This cultural setting involves not just two or more people sending and receiving information to each other, but also artefacts that are used to direct cultural behaviour. The artefacts act as a sort of library of memory cues to remind or suggest to people how to behave according to certain events or locations. In this respect, not just objects but also the wider environment can act as an artefact. 9

So Digital or Virtual Presence is not just a factor of being surrounded by physical three- dimensional space, but of being in another place, taking part socially, and being motivated by tasks.

Place

Ironically, a sense of place is most apparent through its absence, especially in Virtual Environments, be they for games, for tourism, or for heritage preservation. They may have some simulated social interactions, but these social interactions do not richly inhabit or modify their environment. In these environments people are stranded, for place does not recognize their presence.

For Dorothy Massey, place may have any of the following features: a record of social processes; fluid boundaries; and internal conflicts.10 A place is evocative and often fluid, and full of mementos from other places. To view a place as a container of x y and z dimensions is to deny it a cultural content. A place is more like a nexus, or a web. And the strands that conspire to create a sense of place are never set in stone.

Place involves a setting for social transactions that are location based and task specific- for what you do depends on where you are. There is also a need for transition zones of perceived physiological comfort and discomfort-we pick our place depending on personal tastes in comfort, light, privacy, view.11

Finally, a virtual environment has to be writable; a user must be able to leave their mark on it. Whenever we move or sit or place ourselves in the real world-in fact wherever we are, we orient ourselves into the best relationship of task activity, behavioral intention, and environmental features. We will sit x inches into the shade of a tree, a certain point close to the band and the exit and friends but far enough away so that the sound is not so loud, and within a certain visual field range.

Some parts of our walk will be windy dry hot or cold and we will subconsciously try to navigate through all these conflicting, attracting and repelling environmental processes and fields in the best possible way. This navigation is in a sense-placemaking. Territory is place making, in the sense we try to find the best possible site for all conflicting and varying possibilities.

Culturally you could measure this –find the right or appropriate spatial relationship- by measuring say the spatial distances between people in relation to their social prestige and or familiarity. So, the location-placing of self is often cultural (the science is called Proxemics) as well as physiological.

We place artefacts in relation to our perception of how we appreciate or dislike environmental features as well. A bed may be close to the window but turned away so we do not wake up to intense morning light. This might indicate the occupant is a late-riser.

So, our idea of place is identifiable as a locus between environmental features and personal or physical preferences. And also placed artefacts can indicate social relations between people and even between artefacts (houses close or far to each other).

This would support the notion that locating things (placed artefacts) attests to their relative importance or value. And that where one ‘places’ oneself is related to both behavioral and physiological preferences.

Only in a virtual environment, apart from in games (where one hides behind walls and windows, and guns may have a certain range), how one places oneself does not often matter or impinge on a task. You might walk forward to examine something but that is purely to enlarge the object under view. The environment itself has no particular features you wish to avoid or take advantage of. Your only consideration is if you are close enough to an object to fully visually comprehend it. This is not an issue of proximity but of visual acuity screen resolution, and rendering detail. Nothing here is culturally filtered, but physiologically defined.

The complexity of physical placing is also reduced. Without dynamic and directional lighting, you can paint an oil painting, with directional and dynamic lighting you need to consider features of the environment or your hand will permanently or frequently obscure the work.

This is an issue for both moving and stationary spectators of a virtual world. The factors of our journey through an environment and our attempt to maximize the enjoyment through the environment will both colour and enrich our journey experience. The feedback mechanism will also guide our journey through future environments. In future journeys we will not stand too close to the kerb in winter (so we do not get wet), we will not approach prisoners behind bars because they might grab us, we sit down on a clean dry patch of grass. Activities and intentions and environmental factors (climate weather light dark smell sight sound) all have a range that in turn depends on the range of other factors.

This range and more importantly the diffusion and intermingling of this range of interactive forces is almost always absent from a virtual environment (to some extent, range of sight is evident in some entertainment). Space is x-y-z. Space is not phenomenologically or intentionally related in strength to the distance of the force or influence from the user. Nor is digitally simulated space amplified or affected negatively by the presence of other forces or influences.

The virtual environment lacks a 3d matrix of environmental influences.

The question raised is how much engagement and sensory and informational content do we lose or gain? Which factors are in need of restoring and can some of them be recreated digitally or metaphorically?

For example, we will walk under an eave when it rains or when we hear thunder. How would we inspire this behaviour in a virtual world without the ability to soak the user? Perhaps we could use related triggers such as the sound of thunder?

Only if the user

- thought they were in reality or a world that obeyed laws of physics completely and

- were so conditioned that any related trigger made them automatically look for shelter or

- thought that their task would be in some way curtailed by the thunder that they should seek

In fact, a user needs to be motivated (deluded) by the realism of the stimulus or convinced that the sound of thunder had consequences for them if they did not seek shelter.

So, we need to aim for realism or we need to create rewards and punishments. If we opt for realism, the user will eventually lose the automatic reflex as there is no reinforcing stimulus (i.e. they learn they cannot get wet no matter where they are).

If we opt for metaphor, depending on the level of realism, the user will also see through the analogy. There has to be a feedback mechanism somewhere- the question is how? As stationary objects we place or site and centre ourselves optimally inside a flux of forces that affect our task efficiency, our social standing, and our feelings of comfort. As moving objects, we automatically choose the ‘path of least resistance’.

Perhaps not surprisingly, examples of these suggested solutions reside in architecture. Architecture modifies behaviour through symbolic cues, offers paths and centres so that we can navigate and place ourselves, and suggests the passage of time as well as records the meetings of people.

Borrowing from Venetian and Byzantine design motifs, architectural theory of the 1920s, made a distinction between path and centre, to decorate spaces of rest and eschew decoration in paths. Why? For ornaments make us rest, and a lack of ornamentation makes us search without distraction until we find a place we can centre ourselves.

Decoration indicates the goal. And so does formal symmetry-that implies a ceremonial space that is less likely to change. 12 Asymmetry implies influence from outside forces; a more dynamic space better catered for functional tasks than for ceremonial centres.

In VE there is no localization of optimal environmental forces. For the virtual environment is only space, it does not ‘afford’ placing ourselves. So, we only position, we do not place (centre) ourselves. And we do not traverse (as in navigate-set a path) through a sensory field. We walk closer to an object or we stop. In summary, VE lacks paths (optimal navigation) or centres (shelter from hostile environmental forces).

Social Presence

We learn about a culture through dynamically participating in the interactions between its cultural setting (Place), artefacts (and how they are used), and people teaching you a social background and how to behave (through dialogue devices such as stories and commands) along with your own personal motives.13

Some researchers may concentrate on improving technical aspects of creating and viewing virtual environments (such as developing the new version of VRML, streaming media, object re-use, cross platform games engines et al). I wish to instead concentrate on content-development and on feedback mechanisms (although I will also indirectly look at navigation).

Specific aims of a Tourism-related Virtual Environment

We might argue that virtual environments and real-world travel have some very interesting mutual issues. The issues as tabled below include orientation as in understanding the relation between macro and micro without getting lost, and in understanding the relation (cultural historical and physical) between various places.

As people do not want to be bombarded by too much information, there needs to be filtered relevance, ways that users can customise and filter the information.

Many travellers want to have pre-visit experience of a destination, as in knowing something about the place before they spend money and time visiting a place that they do not enjoy. If they do enjoy that destination, they want to be able to record or have a memento of that experience. We might even surmise that if on reaching the destination, the user achieved a goal; that would add to the engagement of the user.

With travel there is the problem of portability, for users want to be able to have means of recording a travel experience and carrying it (along with travel information).

Finally, the experience needs to have some potential aspect of social interaction as people almost always find it more meaningful to be able to share their experiences with others.

| Travel info / experience requirements |

Related Issues in Virtual Environments |

| People have trouble finding places on 2d maps. People are not sure which way is north. |

Orientation and moving from large-scale to small-scale examination of objects is a largely unexplored topic. |

| People want to ‘experience’ place before they go there. They also want to get from A to B to C so they can enjoy their trip. |

VEs typically focus on objects, not objects in use; form should be separable from content so it is easily updateable; users can normally only explore- there is a lack of meaningful interaction. |

| People want to travel light. People want downloadable and portable information. |

Again, an issue of form and content; a lack of profiling; information is not divisible; user choice of interaction or ‘realism’ level could |

|

help reduce bandwidth problems…etc. |

| People want to personalise and filter their information to make it more accessible and relevant to them. They might even want to add personal mementos. |

User-based goals are inseparable from the overall model; VEs typically have no annotation ability; there is no record kept of user-environment interaction history. |

| People want to interact with other travellers. On the other hand, they might want some control over the quantity or even quality of social interaction. |

Most VEs are single-user; sharing of information is usually restricted to chat, sending files or hyperlinks; control of social interaction is limited. |

Interaction, Constraints, Goals, Feedback Mechanisms

The solution proposed in this paper is to create a database that records user-interaction. This interaction is to be with artefacts (objects in the virtual environment), the places users visit (a record of places changing with the passage of time and use), and dialogue (interaction) with agents14 (avatars of computer-simulated people) that users meet.

Design Goals:

Engagement requires a task and objective not just “aesthetic wonder” (i.e. staring at well- designed or artistic objects in appreciation of the design skill). Engagement is not just immersion but immersion plus a task. There is both conceptual and sensory engagement and both need to be obtained in a virtual travel environment.

1. User Goals and Environmental Constraints:

VE needs constraints in order to develop a sense of engagement. These constraints are problems which create objectives i.e. goals.

2. Cultural Constraints:

In travel environments, issues of geography, timing, and ‘cultural perspectives’. Travel potentially involves solving a task despite constraints, and further, in solving a task one has to adopt local methods and perspectives. In doing so, one changes one’s mental model of the environment. Therefore, interactivity is important. This adds to engagement in traveling through a foreign environment. Cultural context requires a setting (task, place, artefact, and intention). The stage or the setting is the scene for initiation into a local perspective.

3. Inbuilt evaluation mechanisms:

To check engagement, we need evaluation devices but we cannot stop people who are in a virtual environment to evaluate their feelings of engagement as that will affect their sense of engagement. Further, on evaluating people after their experience of the virtual environment may be prone to error, as it relies on memory recall and on their noticing what made their sense of engagement powerful or weak or non-existent.

Where a virtual environment seems ‘natural’ to viewers they may not notice important features that a trained expert would deem to be distracting or ineffective. Therefore, we need innate evaluation mechanisms to determine the level and type of engagement without breaking that level of engagement.

So, a virtual environment with social context requires a dynamic and mark-able place, with attenuating environmental forces and features, interactive tasks and event-based

artefacts. It will also need other actors and computer-scripted agents that answer certain questions, and remember who passed by and what they did.

To improve both user satisfaction and feedback, you could incorporate reality back into your virtual environment. Computer-scripted agents may even have a limited ability for recall; actors could leave messages for each other actors via actor-agent dialogue.

Inbuilt evaluation mechanisms

I will now suggest that in order to answer the above issues, and to test user-engagement, four major evaluation mechanisms may help.

1.1.1 ‘Dynamic Place’ For Physical Constraints

- A. Campbell notes:

Cognition

Without the constraints of the physical world, the participant is left with few cues of how to explore and understand the virtual realm.15

To evaluate a virtual terrain with and without dynamic interactive features is an essential step in evaluation of place as opposed to cyberspace.\

With this in mind one could create dynamic places (GIS-enabled database that stores and records localized events and occurrences) along with visual and audial cues indicating changes in climate flora fauna and terrain. Also, parts of the environment could be deleterious to the avatar’s metaphorical health. This will induce the avatar to plan and record (via the map) all paths and journeys so that they do not fall into a stupor (from which they cannot move or wake up from).

The environment will thus range from shelter and familiar territory, to a hostile world depending on task direction, artefacts carried and preservation of health. The more aware and adeptly the user navigates through the environment, the quicker and direct their journey between tasks, and the less the health points that they will have lost.

During the night or during severe simulated climatic change (indicated by the sound of strong wind etc) their health points may be drastically diminished-hence they will be encouraged to look for shelter.

Dynamic physical constraints as an evaluation mechanism controls Environmental Presence– the degree my presence affects the environment and the degree the environmental presence affects me,

1.1.2 Memory maps to record vistas, landmarks and artefacts, encounters

Campbell:

Wayfinding, the dynamic process of using our spatial ability and navigational awareness of an environment to reach a desired destination (Satalich 7), is accomplished by the development of and reference to a cognitive map. A cognitive map is the means by which information about the relative location and attributes of one’s environment is acquired, coded, stored, recalled, and decoded (Moore). Cognitive mapping, “…is particularly important in enhancing the experience of people in places where they are not frequent visitors” (Lang 144). To develop a cognitive map in an unfamiliar, informational, and spatial environment, one must be able to orient and navigate intuitively (Benedikt, “Cyberspace” 123). The architecture should respond to the methods of navigation and should serve to orient the participant to allow the development of a cognitive map.16

Any device for orientation will help users navigate through an environment but a map further allows a graphical history of their virtual travels. If actors are asked to manually select scale and place icons to represent where certain activities or important cues are, then we might be able to track via the size and placement of icons some degree of their engagement. The map can help users plot the quickest or most scenic journey without entering hostile or physically arduous areas (physical constraints) and when users are asked to lead others through the virtual environment (using the ‘teach’ evaluation method) the map will help as a visual teaching cue.

Further, the cognitive map (as it is called in Human-Computer-Interaction studies and town-planning literature) is a long- accepted model of human wayfinding and hence an appropriate tool to evaluate. While research indicates there is no one primary map the same research does indicate that our cognitive mapping is multimodal and hierarchical. Given this, it seems reasonable to presume that a multimodal graphical mapping device that people indirectly customize (indirectly as in the customization arises through task selection) will enable the navigation to be more intuitive and hence usable.

Modjeska, 1997, notes:

Wayfinding is primarily a cognitive process, comprising three abilities [61]:

- cognitive mapping or information generation to understand the environment

- decision making to structure and plan

- decision execution to transform decisions to behavioral actions

That is, wayfinding is a spatial problem-solving process. We could define “skilled wayfinding behavior to be purposeful, oriented movement during navigation” [22].

… A central concept of cognitive engineering, mental models are described as follows: Mental models seem a pervasive property of humans, people form internal, mental

models of themselves and of the things and people with whom they interact. These models provide predictive and explanatory power for understanding the interaction. Mental models evolve naturally through interaction with the world and with the particular system under consideration. [58].17

Imagine that on entering a virtual environment for the first time, that the map is faded and only shows a very blurry concept of what is in the area, as found on maps by neighbours. As one explores the virtual environment, the map becomes more accurate. Perhaps one can even customize from a palette of icons (castles houses bridges, food sources etc) and select and scale and position icons to remind one where one went and what one did and where the safest routes are etc. The map reveals the unknown, a record of the past, and a shadowy gate to the future. Most importantly for us, it could show where people went, and how effectively they avoided the areas dangerous to their metaphorical ‘health’ points.

By allowing users to choose the type of map, we can test user preference between conventional and schematic memory maps. It could be designed in SVG format (Scalable Vector Graphics-refer http://www.adobe.com/svg/overview/richer.html), or in JPEG or animated gif format, with JavaScript interactivity.

1.1.3 Actor-agent dialogues to record dialogue

Many projects are now using avatars for interactive story telling in virtual environments, (for example, http://www.eg.org/events/VAST2001/ or the conversational humanoid project, 3rd Generation, Gesture and Narrative language, at the MIT Media Lab http://gn.www.media.mit.edu/groups/gn/projects/humanoid/ ).

Agents can give out tasks, increase realism, and help navigation. Also, Behr et al.’s 2001 paper describes an avatar that talks and moves is the guide, and visitors can explore but that is all.

Pape et al (2001), proposed creating a virtual guide for historic sites18. Only none of these examples are very interactive. As far as I know, none of these papers suggest agents as evaluation mechanisms. In a 1992 paper, Kelso et al talk of people as “interactors” adding to the “dramatic presence” of social presence and interactivity factors. 19

One of Wickens’ and Baker’s (1995) required features of virtual environments is to be “ from a user perspective rather than from a fixed-world perspective (ego-referenced rather than world-referenced).”20 The need for virtual identities and social presence is also argued for by Greeff et al (2001)21, and Schubert et al, (2000).22

Researchers in Artificial Intelligence and in anthropology such as Schank (1990)23, and Miller (1999)24, believe we learn about a culture through dynamically participating in the interactions between

- Cultural setting (a place that indicates certain types of social behaviour)

- Artefacts (and how they are used)

- And people teaching you a social background and how to behave (through dialogue devices such as stories and commands) along with your own personal motives.

The significance of a place is often learnt by social learning (by people telling you or instructing you). Hence computer-scripted agents that answer certain questions, and remember who passed by and what they did with a limited ability for actors to leave messages for each other may aid social presence. Towell and Towell (1997) suggest that a sense of presence is evident even in 2D mediums, such as chat groups.25

Research indicates social presence is tied with a sense of interactivity. Introducing other actors into a virtual environment only increases the feeling of presence when interaction with others is possible, hence there needs to be genuine interaction with agents. Refer Schubert, Regenbrecht, Friedmann, Real and Illusory Interaction Enhance Presence in Virtual Environments, Submission to Presence 2000. 3rd International Workshop on Presence.

I would like to use actors as the term for users / participants in an interactive virtual environment. This solution thus involves the vehicle for social engagement (the computer-scripted agents), to also act as a vehicle for evaluation and also so that actors can better comprehend and later recall, the social and cultural based context to the virtual environment tasks.

I would argue that by using computer scripted agents we can gain a sense of social presence awareness and identity. We can also use the agents as navigational and task- related cues, and they can record conversation for evaluation of user engagement.

Further, and more specifically for a virtual heritage environment, it is proposed that these agents not only have simple dialogue phrases that participants can engage with to find out information, but that the agents’ memories of these conversations allows us to evaluate the engagement of the participant in an environment.

The agents could record accuracy in communication with actors talking to them. Actors would thus need to learn what questions could be asked. The degree of recall efficiency by agents is related to how culturally appropriate the dialogue is. It would also be very interesting to allow agents the facility over time to have their dialogue corrupted by alien (i.e. non-contextual) phrases of the participants.

Tasks for actors could include, discovering secrets through the use of artefacts and agent dialogue, collect information and or artefacts of interest. At higher levels of interactivity actors can leave messages via agents for future actors.

Sample of Actor’s Dialogue response bar on being questioned by an agent

| [Comment box… ] |

[Nod..] |

[Shake..] |

[Intensity of response in slider bar from Slightly to Fervently.] |

Carrie Heeter argues for a personal presence, social presence, and environmental presence. The former is how much you feel part of a VE (virtual environment), social is how much others exist in VE, and environmental is how much the environment “acknowledges and reacts to the person in the VE.”26

I suggest one further needs a distinction between active presence and passive presence. I have also added a different form of social presence, ‘How much I notice people affecting each other’. We can be aware of social interaction, without feeling part of the society itself. Heeter seems to be confusing awareness of society with social awareness, AND social belonging. To my mind they are all different categories. For example:

- Self-presence

- The degree my presence affects others.

- The degree others presence affects me.

- Social awareness

- How much I feel part of society

- How much I notice people affecting each other

- Social identity

- How much I feel part of society

- How much others think I am part of society

1.1.4 Task-related Artefact to Gauge Cultural Engagement

Michael Meister argues that too often buildings are taught as products and the cultural process that they are part of is often simplified:

[1-2] We art historians too often speak of temples as if built by kings, but they are built for communities; as ritual instruments the use of which changes; one function of which is to web individuals and communities into a complicated and inconsistent social fabric through time. They survive by communities making use of them in a reciprocal relationship of self-preservation quite removed from agendas of historical conservation, Osymandias-like memorialization, or archaeological concerns. … a temple is not one structure, nor of one period or even one community. It moves through time, collecting social lightening and resources. It must be repositioned constantly to survive. 27

A. Campbell notes:

Place

Physical architecture is designed and built to create meaningful places in which society can inhabit and interact (Campbell, “Virtual Reality”). If architecture did not perform this function, it would exist as sculpture in its own universe (Novak, “Liquid Architectures” 243). Architectural place is created in the context of the geographical limitations of the physical site, approached from other spaces and places. A virtual world, without a geographical context and a traditional means of approaching a site, exists in the context of abstract, infinite space. An attempt must still be made, however, to create meaningful places in this limitless space.

According to studies in material culture28, which is advancing into the field of anthropology from archaeology, the way in which objects are used created and exchanged gives us not just new insight into past and long extinct cultures, but also into our own. Material culture theory argues that human interaction is between humans, humans and the environment (and externs-objects that are not artefacts), between humans and artefacts, from humans to humans via artefacts and so on.

The range of interaction is also extremely broad, and in every facet of interaction, artefacts can play a major or even essential part. Hence unlike verbal studies of culture which only account for audial research, material culture studies may offer a wide range of insights across all the domains of interactivity.

That is not to say ‘Material Culture Studies’ is fundamentally a visual-based research field. For example, in The Material Life of Human Beings: Artifacts, behavior and communication, Routledge 1999, page 5, Michael Brian Schiffer argues that even though only 6-7.7 per cent of major research journals in anthropology deal with artefacts or technology, “every realm of human behavior and communication involves people-artifact interactions”.

In response to the above, I propose a game style method incorporating tasks and artefacts to increase user engagement and to educate them on how residents have manipulated the environment. There seems little point in littering a site with cultural artefacts that gained their meaning from how they were used over time, if their only purpose in a virtual environment is to be looked at.

In games tasks are used for engagement hence I wish to motivate the user to learn how to use artefacts in order to solve tasks that will help the user gain knowledge of the virtual environment. [http://www.sierra.com/download/display_results.php?ftp_id=5033. 2001. Sierra Entertainment. Last read December 2001]

“In Capture the Flag, your team must invade the enemy base, steal their flag, and bring it back to the flag in your base to score points. At your disposal are 3 different Armor types, numerous vehicles for both offense and transport, deployable turrets and sensors, and inventory stations that let you select from all available equipment. In Hunters, the objective is to hunt down other players, collect the flags they drop when shot, and return them to the nexus.”

When an actor completes a task, they can view a video or animated gif showing how local residents used the artefact. If they do not view the video that will suggest that they are not fully engaged in learning about the cultural context of that particular task-artefact relationship.

Tasks can be independent of agents and maps and dynamic place factors, but it makes sense to involve agents in tasks if only as carriers of information, as that will increase the richness of interactivity.

The task and artefact creates purpose, is interactive, and prepares to create new levels in the story, reveals how cultures used them. The goal of the actor is to explore every part of the environment and to record on their map where they have gone and what they have seen and done. A subsidiary goal is to gain complete mastery over movement and action through time and space. This is gained by using artefacts to complete tasks, dialogue, and gaining complete view of the memory map.

Artefacts are designed to either reveal how the environment is built or to help the actor travel through hostile environments, and to trade or collect more artefacts. Artefacts carried by an actor has will slow them down but they are more likely to solve tasks.

Not only can one move artefacts between places, one can view annotations (markings on the artefacts recording who used them and where and how successfully). The database will also record the related tasks location and event history of the artefacts, and if it is location effective (only works in certain settings, e.g. a fire stick will not work in strong wind).

If used appropriately, (the right combination of artefact, command, setting, and timing), the artefact can advance history or control an agent to tell an actor more, or can allow an actor to travel through time and space.

An actor can choose between modes of acquiring artefacts (and hence knowledge), a thief, a merchant, a warrior or a priest / magician. Each of the four types has different advantages (if you want to trade something it is better if you are a merchant than the other modes!).

Which mode is preferred may help inform the design goals of future virtual environment projects.

By providing a variety of tasks to actors you could map their enjoyment against varying levels of interactivity.

For example:

- Learn who you are, (social role), and where you are. Depending on the cultural setting, there may be dreams that give coded information. Uncover imposters (other travellers). Actors can interrogate other agents and actors posing as agents. Learn how to gain information via dialogue, response behaviour or situational behaviour from agents.

- Learn how to gain control over artefacts through knowing where to find them, when to collect them, where to use them, when to use them, and their effect on others.

- Travel through time and space (through myths and dreams and artefacts) to reach other virtual worlds. It may be possible through dreams or other devices to show flashes of the current site, or reveal coded messages from past visitors, or extra information at strategic points filtered by user preferences.

- Learn to predict the future events to befall that culture and reasons why.

I suggest that by using different interaction modes against various test groups; by recording dialogues between actors and agents; and by assessing the popularity of various tasks given to actors; we can gain a better idea of what constitutes an engaging virtual environment.

For example, for a virtual tourist environment, actors might be tested against the following modes of interactivity:

- Move through a virtual environment

- Move through a virtual environment with attenuating environmental features

- Collect objects in this virtual environment

- Converse with fictional avatars (agents)

- Converse with avatars (agents) based on real people

- Converse with other actors

- Modify artefacts

- Modify artefacts that record changes and stay modified

- Save the actor’s ‘digital adventure’ saved to his or her own c.

- Annotate the digital information when onsite in the actual real-world location

- Upload personal information back to the site (but only in culturally appropriate placeholders, such as in dreams or on runes) which will be displayed in the right conditions for selected other

You could have up to 5 groups undertaking the above stages. Virtual tourists could explore the environment. Actors could explore, collect objects and converse with agents, as well as affect artefacts and part of the environment. Actors-scribes could be allowed to download a 2d or 3d map that records their adventures in the digital environment.

A real-life tourist group party (of people already embarked on a tour) could experience as much as the actor-scribes PLUS annotate the uploaded digital information in their travel diaries when onsite in the actual real-world location (stages 1-10). Finally, you might even allow part of the real-life tourist group to upload their experiences back into the digital environment and then compare the results across the groups.

Another facet to interaction is augmentation, which I believe is one of the brightest areas of VR-related technologies. I am currently involved with several such projects. One is using GPS and a palmtop to create interactive 3d displays of a 2d-map interface.

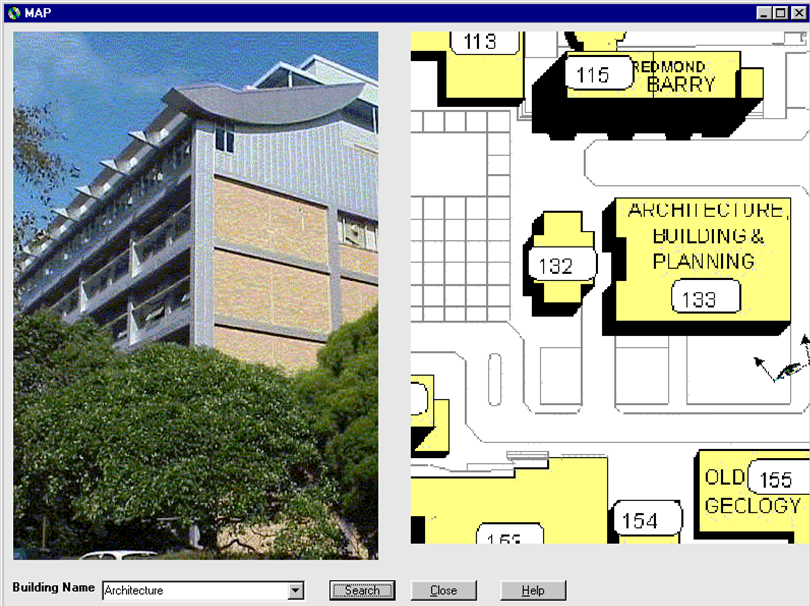

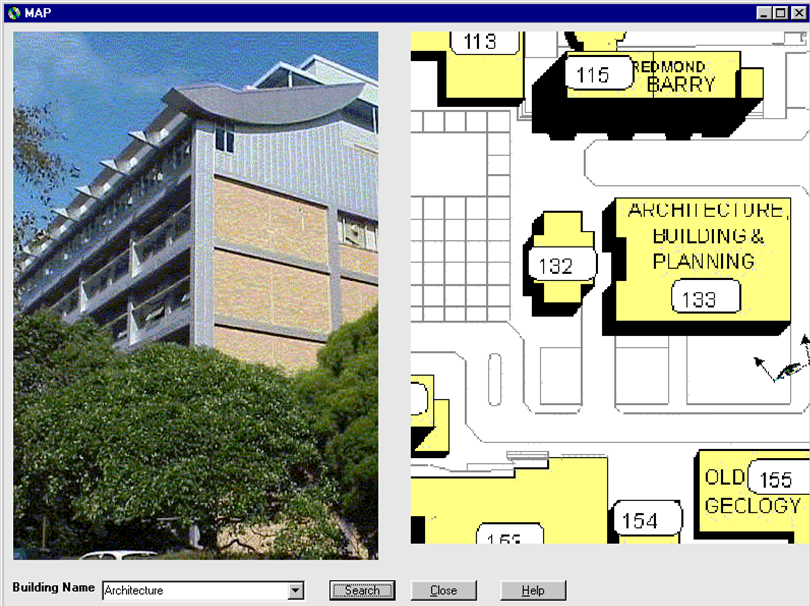

Figure 1 The Shadow Finder: 2d and 3d Mapping Device

The project involved user testing of an A5 sized personal digital assistant specifically catering to guest lecturers and foreign students, new to a campus, and requiring help in finding location-related events. The prototype (entitled the ShadowFinder) had a navigable 2d map of campus, and a GPS told the user where they were on the campus map. As the user changed their position on the map, the 3d screen changed, showing them a Java applet-VRML model of the campus in 3d. They could also pull down a lecture room or facility resource from the menu and the ShadowFinder would search for the map position and 3d view of the entrance for them.

During our testing of the prototype we found that users from the age of 30 to 50 plus, found the 2d and 3d mapfinder far quicker to use and more helpful than the 2d map. They also had surprisingly little trouble in changing the angle of view without getting disorientated.

Another ongoing project, to do with the dissemination of travel information, is using a digital camera with wireless connection to a GPS phone and an image retrieval database. Point the camera at an object and the database decodes the content in relation to your position to tell you what you are looking at.

In the first stage, you point a digital camera takes a photo of a landmark. The image is outlined by light pen and categorised as monument, person painting, sculpture fauna, or flora. The image and category is sent to a database via a wireless connection. The answer along with related information and hyperlinks is sent to your PDA. It might sound ambitious, but all the individual components are commercially available now, I have just not yet heard of anyone who has thought of putting them together. Compared to a wearable tracking device used to create augmented reality, I believe this setup has immediate commercial viability. Already there are digital cameras that can automatically extract images from their background and upload them on the fly to a website.

The results could be compared against a tracking system with a glasstron visor. The viewer will then see a VR environment outlined against the real background. Travelers could use this technology to view simulated Roman amphitheatres with digital actors against the stony landscape that the building once stood on.29 There are several projects attempting to create these mobile augmented versions of past reality, although to my mind they seem to be so ambitious that in-between stages (travel information and travel experience) are being lost in the attempt at a grand synthesis.

This technology could be used to create translucent screens between tourists and landscapes that show the VR past against the real-present. It could also be used for interactive public evaluation of architectural projects; the architects as digital avatars could meet you online and show you around the building-you could annotate details not up to your expectations for other people to view!

However, my real interest is in interactive narratives, augmentation of fact and imagination. For example, actors could erode and change events when situated in history but only when it is in line with what actually happened. This interaction could be blind (it does not matter what you do as long as the results mirror history), or deterministic, like the film Groundhog Day, (your actions have no effect unless they mirror history).

The approach suggested here is constructivist:

Prof. George E. Hein asks:

What is meant by constructivism? 30 The term refers to the idea that learners construct knowledge for themselves—each learner individually (and socially) constructs meaning— as he or she learns. 3 Constructing meaning is learning; there is no other kind. The dramatic consequences of this view are twofold;

- we have to focus on the learner in thinking about learning (not on the subject/lesson to be taught):

- There is no knowledge independent of the meaning attributed to experience (constructed) by the learner, or community of learners…

The professor argues that interactivity in exhibits creates more engagement by allowing the user to apply the tool directly to their own life:

… I have watched adults look at a map of England at the dock where the Mayflower replica is berthed in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Repeatedly, adults will come to the map, look at it and then begin to discuss where their families come from. … here is an interactive exhibit (even if there is little to “do” except point and read) which allows each visitor to take something personal and meaningful from it and relate to the overall museum experience. For me, the Diaspora Museum in Tel Aviv came alive when I had the opportunity to call up family genealogies on the computer in the reference centre. The opportunity to view and manipulate a library of family trees covering several generations and a wide geographical distribution, gave personal meaning to the idea of a Diaspora.31

The final stage of such a process would surely be to create an environment that is modified by the actions of the people travelling (rather than touring) through it. The environment needs to be not just dynamic but also have a memory. In terms of technology, it is proposed to create a virtual terrain where even the leaves on the trees can fall off in a strong gale. For example, Blueberry3d has a GIS database and creates fractal trees and terrain. It can also simulate wind rain fog and sun glare as well time of day (from the workstation or from the database). It imports DEM map models and 3d Studio max objects. It has a physics engine and displays only what is on the monitor and at a level of detail that the hardware can support.

Commercially available game engines are another way of combining land-based data with user-interaction and task-based cultural immersion.

Comparison to various VE types of evaluation

Celentano and Pittarello (2001), argue that the users should be asked to come up with specific scenarios in response to a meta-author guideline system.32 The world-builder will then enact the scenarios. Celentano and Pittarello call this a user Centered design approach and refer to D A Norman’s and S W Draper’s paper User Centered System Design (1986).

Due to the chat nature of agents, one could also run a cognitive walk-through of possible dialogue with a low-level prototype.

I would argue that many users helping to create a virtual environment would be very difficult with current technology. However, I have suggested that if actors could augment

such a site with their own mementos (the actor-author stage) that this may improve the sense of engagement. This suggestion is thus for content augmentation rather than for model creation per se. For subjective evaluation Lombard et al suggest the paper and pen approach i.e. the questionnaire.33 I agree, but have placed the three criteria of physical space, engagement, and realness or naturalness on a spectrum with negative feelings the converse of engagement.

| Negative |

Presence factor |

Positive |

| ß |

Physical Space/ spatial presence/ |

à |

| ß |

Engagement/ involvement/ Involved control |

à |

| ß |

Naturalism/ interface quality/ realism. |

à |

It may be that fixed questionnaires may not be the most useful form of subjective evaluation. Woodruff et al (2001) et al propose informal evaluations with open-ended questions for “unexpected uses and results”. 34

Kim, 199935, uses a Prequestionnaire to ascertain users’ domain knowledge, i.e. how often they used computers. Also, their task needs, i.e. how often they visited a shopping mall, and for which items. The paper lists time spent on pages to ascertain what caught user attention. I also suggest a study of user domain knowledge, and objective tests on task performance, and dialogue accuracy via actors interrogating the agents.

Or, Lombard et al suggest an ethnographic approach: (see McGreevy, 1993; Gilkey & Weisenberger, 1995). For example, in Ethnography and information architecture, Mark Rettig, (2000:p21) argued that information design tools were very similar to those used in archaeology and anthropology research.

♦ Observation (shadowing, people watching, examine ‘artefacts’).

♦ Interviews (contextual, storytelling).

♦ Sampling (randomly, users are asked to sample events).

♦ Self-reporting (users take pictures or keep journals etc).

We can incorporate the above methods in a virtual environment; for example, we can note which artefacts users take with them on their virtual travels. We can check the usability of a travel diary / map, which acts as an on-screen inventory and memory recall device for actors. We can observe what people do by replaying videos of their journey, and we can check actor-agent dialogue to see how quickly and easily actors learn to ask the right questions.

In terms of social presence, we can ask actors which agents they most enjoyed chatting to, which types of agents they would most likely leave messages with or ask questions. We could even ask if actors could enter the world posing as agents, when or if they discovered if they were chatting to agents or to real people posing as agents, and if this enhanced their sense of engagement.

Further, some research in literature (and as mentioned, in MUD style chatrooms), implies immersion does not have to be spatial:

… You can, it seems to us, read as though your central purpose were to “make contact” with another human being (Vipond and Hunt, “Point Driven Understanding” and “Shunting Information“). This may, in fact (as Rosenblatt has suggested in a personal communication of 1985) be a subcategory of aesthetic reading..

… In other words, reading is a transaction…

… In general, we have found that the readers who seem most engaged in, and who feel most satisfied with, their readings (of these texts, in these situations) appear to act as though the purpose predominating in their reading were to make social contact, by sharing evaluations, with a narrator or author who is assumed to be somehow “behind” or “implicit in” the text… engage in the kind of transaction with it that is, after all, the whole point of literature.” 36

Given the above, we could evaluate user engagement with dialogue-only agents as opposed to 3D-modeled agents with lip-syncing and the same dialogue to see whether the 3D aspect does increase engagement, and which levels of interactivity are the most useful for conveying a sense of engagement.

1.1.5 How the ideas will be tested and evaluated Proposed evaluation environment

Evaluate a group of spectators who explore the environment, and gradually add more levels of interactivity; does their sense of engagement increase?

Woodruff et al (2001) suggest 3 navigation paradigms for virtual environment travel, utilising vary levels of knowledge of navigation, goal or location. There are 3 suggested users, tourists, students and experts. Tourists have constrained range of movement, experts can go anywhere at once, and have access to more information (both short and long text). Students are in the middle. In a similar fashion I propose the following types of users: tourists, actors, and actor-authors.

In the proposed prototype, there are three types of users, who are given varying levels of interaction. Tourists can explore the environment. Actors can converse with fictional avatars (agents), with avatars (agents) based on real people, and with actors pretending to be agents. Actors are also given tasks to perform, and they will need help from clues given by agents. Actors-authors can annotate and record both on their memory amps and on artefacts, their adventures become part of the virtual environment.

Prior to the experience in a small focus group we could ask users their experience of computers, 3d worlds, and virtual tourism. Further domain knowledge could be ascertained as to how well they know the history of the virtual world site.

During the experience the database can record user performance times and preferences, say how quickly they learn to ask agents the right questions, how quickly they learn to leave messages for each other via agents, and which types of agents they most often approached.

After the experience, we could evaluate presence by asking users to rate the following factors on a five or seven-point scale of presence factors as shown previously (and below).

| Negative |

Presence factor |

Positive |

| ß |

Physical Space/ spatial presence/ |

à |

| ß |

Engagement/ involvement/ Involved control |

à |

| ß |

Naturalism/ interface quality/ realism. |

à |

Waterworth in an undated online paper 37 proposes that virtual environment evaluations range from an objective “outside-in” (external expert) to subjective “inside-out” spectrum. We could also specifically evaluate a sense of being immersed via engagement, both internally (by the user), and externally (by the observer). So, we could develop an evaluation model as below:

| Internal (self) observation |

External (other) observation |

| Task Immersion |

| How much I am engaged/distracted in a task |

How much I seem engaged/distracted in a task |

| Environment Immersion |

| How much I am engaged/distracted in an environment |

How much I seem engaged/distracted in an environment |

| Sense of being surrounded |

| How much I am surrounded by an environment |

How much I seem surrounded by an environment |

Conclusion

The suggestion was that we could evaluate engagement by varying the levels of interactivity across 3 types of users, tourists, actors, and actors who can act as additional world-authors. The method thus proposed is:

- Using scripted agents as dialogue aids – agent-actor dialogue – to help actors via appropriately worded

- Allowing people to update the memory maps with their own positioned and scaled icons.

- Having the changing factors in dynamic environments have an effect on how people move through virtual environments through the metaphorical notion of ‘health points’ as borrowed from game

- Enabling actors to view the effects of how they choose to complete tasks via thartefacts at their disposal.

- Creating a world where individual autonomy and remembrance of individual actors is integrated with actual historical events and figures (augmentable history).

Later research might like to explore the implications of actor-actor messaging in augmented reality environments, with actors being able to leave future actors multimedia messages and annotations, or actors being able to interrogate agents on previous encounters with other actors. It would be an interesting test of social presence if actors were challenged to identify other actors pretending to be agents.

Once inspired by this new cultural knowledge, my hypothesis is that people would like records of their virtual travels via downloadable ‘cognitive memory maps’ (records or playbacks). Perhaps travellers would find it useful if they could annotate these memory maps with their real-world travel experiences.

I further suspect that if actor-authors could augment the virtual environment with these real-world notes (i.e. upload notes back to the virtual environment so other people could read these travel diaries), that their and other actors’ engagement would be further enhanced.

1 ICOMOS Burra Charter Guidelines: Cultural Significance 1998 (http://www.icomos.org/australia/burrasig.html)

For exclusion of digital media for recording see in particular section 4.3:

Graphic material “Graphic material may include maps, plans, drawings, diagrams, sketches, photographs and tables, and should be reproduced with sufficient quality for the purposes of interpretation.”

Currently virtual heritage models fail most if not all the criteria for collection of information (see ICOMOS Burra Charter Guidelines: Cultural Significance 1998- a revised edition was promised to appear in 1999).

2 Archaeological terms include trace, artefact (platial, personal and situational), interactor (humans are complex interactors), and life history. Refer Schiffer, Michael B., The material life of human beings : artifacts, behavior, and communication, Michael Brian Schiffer with the assistance of Andrea R. Miller. Published London; New York: Routledge, 1999.

3 Schiffer (Schiffer 1999 p16), gives a long list of academics in the social and behavioural sciences using the metaphor (including Giddens 1993, Braun 1983, O’Brien et al 1994, Deacon 1997, Goffman 159 and 1974, Hall 1963, McDermot and Roth 1978, Byrne 1995, Nielsen 1995, Walker 1998). Schiffer further extends the actor / performer metaphor as below but in reference to what he calls anthropological archaeology and its attempt to re-focus on people-artefact interactions. The terminology focuses on material culture interaction, using interactor, artefacts, and externs as the basic elements.

A major part of Schiffer’s theory relies on a three-way means of communication (Schiffer 1999: p59); information is transmitted person to person via artefacts, not directly person to person (‘receiver-sender’) as in linguistic theories. A person modifies an artefact, which is decoded eventually by an archaeologist’ s ‘relational knowledge’. There are thus three interactors.

4 In Ethnography and information architecture, Mark Rettig, (presented at the ASIS Summit on Information Conference 2000:p21) argued that “people perform tasks on objects with tools in context”. If this is true, one needs a clear relationship of people-people relationships, challenging tasks, manipulable objects, responsive tools, and thematically appropriate setting (both physical and historical).

The terminology between information design and archaeology is also similar, adding weight to the use of a related terminology, as it appears to be in some currency across disciplines. And an inter-disciplinary acceptable terminology must surely be a requirement in the discussion of virtual environments for cultural learning.

5 Where actors actually control an avatar or a role-based character in a digital environment, there might be use for a puppeteer analogy. Where the actor is actually the puppeteer and the avatar is the puppet and the strings or rods are the exploratory/interactive methods, one criterion of immersion could be how fully the puppeteer begins to feel he or she is actually the puppet.

One way of describing the overall elements of a digital environment might be to borrow from performance media. Terms that could be used include actor (the visitor to a digital environment); the backdrop (the default environment); the audience (those observing but not taking part); props (artefacts and naturally occurring objects); dialogue (in multi-user chat rooms); cues, motives, and plot devices. There may also be improvisation (as metaphors for triggered events, agent behaviours, predefined scripts, and random or actor-directed actions and events not pre-defined).

6 In more advanced digital places, there may be other people also visiting that you can talk to, at least one digital place has the capacity to ‘build’ simple virtual dwellings, and you can ‘shop’ online (refer version 3.2 or later of ActiveWorlds, http://www.activeworlds.com).

7 I have been told that Michael Heim’s work is an exception, but I have not been able to find information on the website given to me (http://www.mheim.com) to personally verify this.

8 This issue is evident even in the debate over using the terms Virtual Reality or Virtual Environment. One person who believes virtual reality is the default standard offers the following definitions:

“Virtual Reality is the use of computer technology to create the effect of an interactive three- dimensional world in which the objects have a sense of spatial presence.”…

”Virtual Reality is the use of computer technology to create the effect of an interactive three- dimensional world in which the objects have a sense of spatial presence.”)

[Steve Bryson, NASA Ames Research Center, http://www.fourthwavegroup.com/Publicx/1725w1.htm].

9 If VE cultural coding is possible, value adding (in terms of entertainment), or educationally significant. In order to answer these 3 questions, we have to have a theoretical model of cultural learning.

10 Doreen Massey in a short essay entitled ‘A Global Sense of Place’ in Marxism Today and also Studying Culture An Introductory Reader Published London; New York: Arnold; New York, NY: Distributed exclusively in the USA by St. Martin’s Press, 1997.

11 Location-place making:

Whenever we move or sit or place ourselves in the real world-in fact wherever we are, we orient ourselves into the best relationship of task activity, behavioural intention, and environmental features. We will sit x inches into the shade of a tree, a certain point close to the band and the exit and friends but far enough away so that the sound is not so loud, and within a certain visual field range.

Only in a virtual environment, apart from in games (where one hides behind walls and windows, and guns may have a certain range), how one places oneself does not often matter or impinge on a task. You might walk forward to examine something but that is purely to enlarge the object under view. The environment itself has no particular features you wish to avoid or take advantage of.

Your only consideration is if you are close enough to an object to fully visually comprehend it. This is not an issue of proximity but of visual acuity screen resolution, and rendering detail.

Nothing here is culturally filtered, but physiologically defined.

12 Adrian Snodgrass wrote how traditional architecture around the world symbolised a relationship between an inner pure physical space (a square or circle) that symbolised unity and timelessness, to an outer relationship of shapes that symbolised diversity. In his opinion, traditional forms of architecture symbolised a journey from unity to diversity as an explanation of the divine primal source and origin of the universe.

13 For a discussion of how we evaluate intelligence of others through story-telling ability, and how we remember things through making stories of them, please refer to Schank, Roger C., Tell me a story : a new look at real and artificial memory, Published New York : Scribner, c1990.

14 http://www.roddy.net/kim/SyntheticActors.htm#Previous%20Research What is an Agent?

“Due to the broad use of the word “agent” in various computer hardware and software literature and research, one must always make certain assumptions when this term enters a discussion.

Similar to many words in the English language, context often allows one to focus on a specific definition, or at the very least, eliminate definitions that don’t apply. Since the context of this paper is VE, and therefore computer-generated, situated environments, one could assume the following characteristics apply with regard to an agent definition:

A software object or self-contained program.

Able to sense it’s environment to some, possibly imperfect, level of fidelity, including its own internal state. Motivated by self-contained intentions or goals.*

Capable of making independent decisions based upon it’s perceived environment. Takes actions as a result of these decisions, which can affect itself or its environment.*Internal goals, as opposed to external goals, actually make agents autonomous. Although technically, plain agents are different from autonomous agents, autonomy is often assumed when speaking of Synthetic Actors.

Based on the above assumptions, a reasonable generality for agents in this context could be the following definition:

An agent is an autonomous software object that is capable of making decisions and taking actions to satisfy internal goals, based upon its perceived environment.”

15 Campbell, D.A (1997). Explorations into virtual architecture: a HIT Lab gallery. IEEE Multimedia, Volume: 4 Issue: 1, Jan.-March Page(s): 74 –76

16 Ibid.

17 Modjeska, D., , Navigation in Electronic Worlds: Research Review for Depth Oral Exam, Department of Computer Science 1 May 1997 navigation in virtual worlds paper http://citeseer.nj.nec.com/cache/papers2/cs/7/ftp:zSzzSzftp.cs.utoronto.cazSzpubzSzreportszSzcsr izSz370zSztr-370.pdf/modjeska97navigation.pdf

18 Pape, Dave, Josephine Anstey, Sarita D’Souza, Tom DeFanti, Maria Roussou, Athanasios Gaitatzes. “Shared Miletus: Towards a Networked Virtual History Museum”, Proceedings of the International Conference on Augmented, Virtual Environments and Three-Dimensional Imaging (ICAV3D), Mykonos, Greece, 30 May – 1 June 2001. [http://www.evl.uic.edu/pape/papers/miletus.icav3d01/miletus-icav3d.pdf last read October 12, 2001]

19 Kelso, M.T., Weythrauch, P., & Bates, J. (1993). Dramatic presence IN Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 2(1), 1-15.

20 Wickens, C., & Baker, P. (1995). Cognitive issues in virtual reality. In W. Barfield & T. Furness, (Eds.), Virtual Environments and Advanced Interface Design. New York: Oxford University Press.

21 In their iCHIM2001 paper, Interactive Cultural Experiences using Virtual Identities (2001), Greeff and Lalioti argue that virtual identities are needed to allow engagement in “interactive cultural experiences”. “People create meaning through narrative or stories ..Culture influences our perspectives, values and behaviour..Many applications, such as culture, are dynamic and therefore static representations are not efficient for portraying them.”

22 Research indicates social presence is tied with a sense of interactivity. Introducing other actors into a virtual environment only increases the feeling of presence when interaction with others is possible. Refer Schubert, Regenbrecht, Friedmann, Real and Illusory Interaction Enhance Presence in Virtual Environments, Submission to Presence 2000. 3rd International Workshop on Presence.

Thomas Schubert, Holger Regenbrecht, Frank Friedmann, University of Jena, Germany DaimlerChrysler AG Research and Technology, Virtual Reality Competence Center, Ulm, Germany igroup.org Presenting author: Thomas Schubert, http://www.uni- jena.de/~sth/vr/abstract_presence2000.html.

23 Schank, R. C. (1990). Tell Me A Story A New Look at Real and Artificial Memory, USA: Colier Macmillan Publishing Company.

24 Miller, D. (1997). Material Cultures, Why Some Things Matter. London: UCL Press.

25 Towell and Towell, (1997):

“It has been suggested that degree of presence in a communication medium is related to two factors, vividness of the environment and interactivity, the degree to which the users may influence the form or content of the mediated environment (Steuer, 1992)… Interactivity includes such things as social presence, or the degree to which the environment contains other people who are reacting to you (Heeter, 1992)… [this research] indicates that a sense of presence was reported by 69% of those connected to these virtual environments.”

26 Heeter, C. (1992). Being there: The subjective experience of presence IN Presence, Teleoperators, and Virtual Environments, 1,262-272. [http://www.commtechlab.msu.edu/randd/research/beingthere.html]

27 THE GETTY PROJECT: SELF-PRESERVATION AND THE LIFE OF TEMPLES Michael Meister, [Paper presented at the ACSAA Symposium, Charleston SC, November 1998] http://dept.arth.upenn.edu/meister/acsaa.html

28 Material Culture References include: Material culture / Henry Glassie; photographs, drawings, and design by the author. Published Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999.

29 There are other researchers in this field, for example at Columbia University, http://www.cs.columbia.edu/graphics/projects/mars/mars.html. For products please refer http://www.pangonetworks.com, http://www.mvis.com etc.

30 The Museum and the Needs of People CECA (International Committee of Museum Educators) Conference Jerusalem Israel, 15-22 October 1991 Prof. George E. Hein Lesley College.

Massachusetts USA Constructivism http://www.exploratorium.edu/IFI/resources/constructivistlearning.html [© 1996 Exploratorium, 3601 Lyon St., San Francisco, CA 94123]

31 Online article by Hein, G.E. 1991 (written). Constructivist Learning Theory, Institute for Enquiry. http://www.exploratorium.edu/IFI/resources/constructivistlearning.html website dated 1996. From a paper presented to The Museum and the Needs of People CECA (International Committee of Museum Educators) Conference, Jerusalem Israel, 15-22 October 1991 by Prof. George E. Hein of Lesley College. Massachusetts USA.

32 Celentano, C., and Pittarello, F. 2001. A Content-Centered Methodology for Authoring 3D Interactive Worlds for Cultural Heritage, in D. Bearman, F. Garzotto (ed.), ICHIM ’01, International Cultural Heritage Informatics Meeting, Milano, September 3-7, 2001. (http://www.dsi.unive.it/~auce/docs/ichim01a.pdf Pdf size 260Kb).

33 Lombard, M., (2001). Resources for the Study of Presence-Online web resource compiled from Presence List Serv Group. http://nimbus.ocis.temple.edu/~mlombard/Presence/measure.htm last viewed November 8, 2001.

Also see: Lombard, M., Ditton, T. B., Crane, D., Davis, B., Gil-Egui, G., Horvath, K., Rossman, J., & Park, (2000). Measuring presence: A literature-based approach to the development of a standardized paper-and-pencil instrument. Presented at the Third International Workshop on Presence, Delft, The Netherlands. http://nimbus.temple.edu/~mlombard/P2000.htm [For more information about this project and/or to download the complete measurement instrument: http://nimbus.temple.edu/~mlombard/p2_ab.htm] last viewed November 8, 2001.

34 They note that visitors preferred audial information to text, “Many visitors (both frequent and infrequent attendees stated that they had a strong desire to interact socially during the visit.”

-“knowing what others had just learnt (either by shared listening or overhearing) provided a basis for different interaction.”

-Visitors wanted to dynamically balance guidebook; room; and social interaction (with companion). Woodruff et al define “the basic principles of usability (efficiency, ease of learning and satisfaction.)” Refer: Woodruff, A., Aoki, P., Hurst, P., Szymanski, M. (2001) Electronic Guidebooks and Visitor Attention. ICHIM2001 paper. http://www.archimuse.com/ichim2001/abstracts/ last viewed November 6, 2001.

35 Kim, J., An empirical study of navigation aids in customer interfaces, in Behaviour & Information Technology, 1999, v18 no.3., pages 213-234.